Tiger in Twilight

Tiger Woods is back. But is he back like before?

CreditCreditSam Hodgson for The New York Times

Supported by

Tiger Woods still has the most famous silhouette in sports, even after all these years.

From behind, the V-shaped back that tapers to the same 32-inch waist. From the front, the same muscular arms gripping a club, right hand over left, in that quiet moment before he coils. Relaxed in the fairway, one hand resting atop a club, the other on a hip, one foot crossed over the other.

All of them classically, identifiably Tiger Woods. Time and age haven’t altered the outline.

Woods is 42 now. He has not won a tournament in five years, a major in 10. He thought as recently as a year ago that he might never play competitive golf again because he could barely stand up. Golf would have to soldier on with stars named Dustin and Justin and Brooks. None of them Tiger, or anything like him.

Yet here he is, Tiger in twilight, and he looks the same, mostly acts the same, and is finally playing somewhat like the man everyone remembers, back in those good years before health and scandal took an ax to his growing legacy.

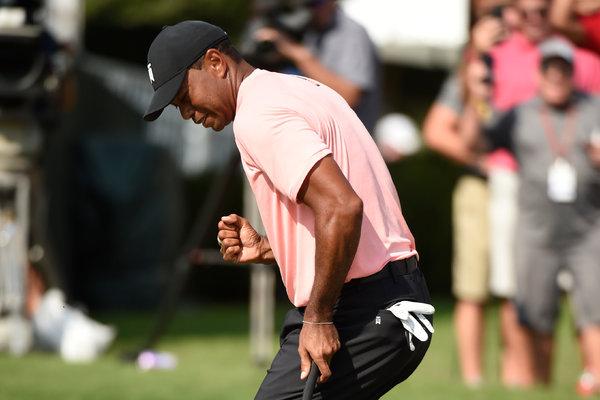

He even reintroduced the celebratory uppercut on the 18th green at the P.G.A. Championship in August, puncturing the steamy St. Louis air, and it was strange only because he did not win. But even in second place, it signaled that he was back.

He knew it. The swelling galleries and television audiences knew it. Those who started wearing red T-shirts with the silhouette of his uppercut and the words “Make Tiger Great Again,” they knew it, too.

Funny, that borrowed allusion. Woods rejoins the cultural landscape in 2018, a far different time and place than when he was last great — everywhere but a golf course, at least. That his re-emergence comes in the Age of Trump is a delicious coincidence, wrought with complexity that Woods would rather avoid.

A golfer who still may be the most famous multicultural athlete on the planet. A president cleaving the country on cultural and racial lines. Occasional golf partners, Woods designing a course that will have Trump’s name on it, Woods evading the subject of their relationship — “We all must respect the office” — while Trump tweets his appreciation.

Somehow, none of that matters. Not here. Not if Woods can help it.

He comes back into view with his familiar walk — purposeful, confident, shoulders up, eyes locked forward. Nobody walks like him, just like nobody swings like him or stands like him.

“Tiger!” cry the voices, too many to count. Nobody calls him “Woods,” even in middle age.

Fans freeze and go quiet as he gets close and stops, as if the Sunday school teacher just walked in. They aim eyes and cameras at him. That’s one change from a few years ago — everyone with a cellphone, as many cameras as faces, practically.

Zoom in. The only visible sign that he is older, beyond the faintest hint of age in his boyish face, comes after he completes the 18th hole.

The familiar applause carries him off the green, and he removes his “TW”-branded cap for a few moments, as golfers do as a gesture of decorum.

His hairline is in slow retreat. It is a thinning ring, like a faded halo.

More Approachable, But Better?

The working angle of his latest act, filled with presumption as much as proof, is that Woods is different now — humbled by the lost years, appreciative of the ongoing support, relieved at the opportunity to be here again.

But is he different? Maybe he’s more relaxed. Chattier during a round, though Woods disagrees. Veteran reporters and close friends say he’s lightened up, more like what they see in private. The testiness that used to accompany bad days has dissolved.

That all seems true, if you’re looking for it. Maybe it’s age and appreciation. Maybe the stakes and expectations haven’t been high enough yet.

To trail Woods at a golf tournament each day, from the moment he arrives to the moment he leaves, is to see two sides of a man who works hard to show only one. There is a person and a persona.

Fans don’t make the distinction. They like the familiarity. They roar in his ear when he makes a good shot. They smile in his wake no matter the blankness of his expression. They want it to be 2008. Make Tiger Great Again.

“We love you, Tiger!”

“You’re still the man, Tiger!”

“Welcome back, Tiger!”

Woods has always had some ill-defined “it” factor that drew our attention. It is even harder to explain now.

Is it all about his ability — or his former ability — to play golf? His personality? His charity work? His skin color, as the son of an African-American father and a Thai mother, which still stands out in the starkly white establishment of golf?

These days, is it more about where he has been than where he might take us? Appreciation or expectation?

You wonder what he could do to irretrievably break the hold. You wonder if parents tell their children about the mistresses and the famous Thanksgiving car crash into the neighborhood fire hydrant, about the prescription pills and TMZ headlines and police mug shots as recently as last year after an arrest on charges of driving under the influence.

But golf is a self-conscious world steeped in decorum. It is not a typical sports arena. There is no tolerance for insults. It is no place for scorn. In a week in New Jersey, Woods heard more Bon Jovi references than heckles.

(It is true. Tommy Fleetwood, one of Woods’s playing partners, was serenaded with “Tommy used to work at the docks … ” just as he struck a putt.)

So the masses go along, in their polo shirts and belted shorts, racing from one shot to the next. As Woods nears, they stare at him, like something caged in a zoo. Giddy from proximity, and maybe a few beers, they whisper about him in golf voices.

He looks good, dude. He looks fit. (He weighs between 180 and 185 pounds, same as he has for 20 years. Having slowed his fitness routine because of his back — more resistance training and stretching, fewer weights and less running — he tracks this with a full-sized doctor’s scale in his Florida kitchen.)

You see his entourage anywhere? Wonder if his girlfriend is here. (Over there, behind you. It’s Erica Herman, Woods’s 34-year-old live-in girlfriend of two years, standing with Rob McNamara, 43, Woods’ right-hand man. They follow every hole, inconspicuously strolling behind the mobs.)

Oooh, what’s he eating? (It’s peanut-butter-and-banana on pumpernickel. His caddy makes it for him.)

Wait, where’s he going? (To the portable toilet.) Oh, there he is. He’s back. Way to go, Tiger! He goes to the bathroom just like us! And so it goes, hole after hole, day after day.

In return he gives his talent and reputation and an averted gaze. Not much more. Woods always felt like a mash-up of robotics and marketing. Cold constraint was wired into the design.

Injury and Scandal Take A Toll

Forty-two is an awkward age for a professional golfer. If talent and desire have not abandoned you, youth and strength have probably passed you. Most contemporaries are gone.

Woods’s career is usually divided into Before Thanksgiving 2009 and After Thanksgiving 2009. That was the night that a tabloid-perfect infidelity scandal erupted. Woods crashed his Escalade near his home and his wife, Elin Nordegren, smashed the window with a golf club.

A parade of women emerged to say they had affairs with Tiger Woods. Sponsors tiptoed away. Woods went to rehabilitation for sex addiction. He and Nordegren, parents of a 2-year-old girl and an infant boy at the time, divorced.

He rebuilt his career, slowly, in the bubble wrap of the golf world, where naysayers are fenced out and ticket sales and television ratings jumped with every precious Woods appearance. A victory in 2012. Five more in 2013. The lost No. 1 ranking, restored.

Then, the lower-back problems. There were three microdiscectomy surgeries in 20 months. There were only 19 starts from 2014 to 2017. His best finish was 10th.

In desperation, Woods had a fourth back surgery — this time, spinal fusion in April 2017. It removed a disc and grafted two lower-back vertebrae (L5 and S1) into one less-mobile one, like welding two rusty and unreliable links of a chain together.

“If it doesn’t fuse, there really is no other option,” Woods recalled last week.

Weeks later, in May 2017, he was found asleep at the wheel of his running car. Toxicology reports found prescription painkillers and sleeping pills, plus an active ingredient in marijuana, in his system. Woods pleaded guilty to reckless driving and went to treatment.

He did not swing a club for months. Then reports circulated around the tour. Players had been with Woods at home in South Florida and said that he was hitting again, looking and feeling good. He got rid of his coach. He swapped out every club in his bag. Tiger is coming back, they said. For real. Just watch.

And here we are, watching. And here he is, having finished second in the P.G.A. after being sixth in the British Open, looking like the good parts of the past are possible again.

Woods’s swing looks virtually the same to anyone who has seen him over the past 10 or 15 years. The effect of the fusion surgery may be mostly in his follow-through, as he tends to lift up his shoulders a fraction of a second earlier than before.

He still swings the club 120 miles an hour, faster than most. The drives don’t fly quite as far as they used to, but farther than most. Accuracy off the tee and putting have been his peskiest issues, but he still had the Tour’s 10th-best scoring average at the end of August.

Now he’s off to the Ryder Cup, and a $9 million pay-per-view match with longtime rival Phil Mickelson in November, and there is already talk of (and betting lines for) Woods winning a major in 2019. After all, the U.S. Open is at Pebble Beach, where he won by 15 strokes in 2000, and the P.G.A. is at Bethpage Black, where he won the 2002 U.S. Open. And before any of that is the Masters, which Woods has won four times.

A year ago, it looked like Woods might never play again. Now it feels like he could play to 50, if the gods of injury and scandal keep their distance.

He is not the best golfer, not now, maybe not ever again. But he’s not just another guy, either.

He Plays Golf with Trump But Avoids Talk of Race

Woods saves most of his smiles for those he knows. With galleries at a distance, he laughs hard at jokes on the driving range, sometimes the tee.

On one hole during a Tuesday practice round, with few fans around, he waved to players at a nearby green with a raised club. On the shaft was a vertical middle finger, on his face a smile. He did it twice. The others laughed.

As Woods spoke to reporters after his final round in New Jersey, Bubba Watson and Harold Varner III leaned out a window to heckle him. “We love you!” Varner called out. Woods smiled and tried to focus on the next question.

He can be chummy with reporters. When one stood next to the green during a practice round, Woods approached and, with an expletive, said, “Get away from my bag,” and laughed.

He seems a man happiest to be viewed from a distance, in two dimensions. A silhouette. No surprise that he has a yacht named “Privacy.”

Woods’ desire for a buffer from reality translates to the mystery surrounding his core beliefs. In 1996, when he was 20, Nike released an ad with Woods that read, in part, “There are still courses in the U.S. I am not allowed to play because of the color of my skin.”

He has since rarely foraged into any thorny racial, cultural or political issue, to the frustration of some. Either he has few strong opinions or he figures that there is little to gain by expressing them publicly. Either way, golf’s demographics do not encourage it.

But 2018 is a different era than the last time Woods captured the collective imagination. Trump, especially, is working the backhoe on the racial divide, finding sports to be a place to roil debate. He has ranted against athletes who knelt during the national anthem and sparred with LeBron James on Twitter.

Woods and Trump have homes not far from one another in Florida. They have dined together, Woods said. They have played golf, before and after Trump became president, including last November at Trump National Golf Club in Jupiter, Fla. (The foursome included Dustin Johnson and Brad Faxon.)

Woods is designing the course for Trump World Golf Course Dubai, scheduled to open next year. The project took root before Trump’s company took on management, but the website for Tiger Woods Ventures, referred to as TGR, an umbrella organization over all of Woods’ business and charitable work, does not dodge the association.

“I’m enjoying working with The Trump Organization, which is first-class,” Woods says on the site.

Woods was absent from golf for most of 2017, and went most of the year without being asked about Trump or these divisive times. Through his agent, Mark Steinberg, Woods declined a request to discuss his thoughts for this article.

So I asked the questions at a news conference after Woods finished his final round at The Northern Trust, where he finished in a tie for 40th. The interaction took 60 seconds.

“Well, I’ve known Donald for a number of years,” Woods said. “We’ve played golf together, and we’ve had dinner together. So, yeah, I’ve known Donald pre-presidency and, obviously, during his presidency.”

What do you say to people who might find it interesting that you have a friendly relationship with President Trump? I asked.

“Well, he’s the president of the United States,” Woods said. “You have to respect the office. No matter who’s in the office, you may like, dislike the personality or the politics, but we all must respect the office.”

I asked Woods — the son of an immigrant mother and an icon to minority communities, on a first-name relationship with a president many people of color consider a racist — the least-specific question imaginable, the news-conference equivalent of open-mike night.

“Do you have anything more broadly to say about the state, I guess the discourse, of race relations in this country?”

“No, I just finished 72 holes,” he said, looking for levity. “And really hungry.”

He amicably answered a few more questions from others about golf. Trump tweeted his appreciation of Woods the next day.

“The Fake News Media worked hard to get Tiger Woods to say something that he didn’t want to say,” Trump wrote. “Tiger wouldn’t play the game — he is very smart. More importantly, he is playing great golf again!”

A Superstar Driving the Courtesy Car

Tiger Woods lives what he thinks is a fairly normal life, which is what people who live extraordinarily abnormal lives usually think.

His mother, Kultida, lives a few minutes away. So does Elin, now his ex-wife, and they share custody of Sam, their 11-year-old daughter, and Charlie, their 9-year-old son. Woods takes the children to school and soccer practices. Just another guy.

And then he walks out of his custom-built mansion in Jupiter Island, Fla., past the swimming pools, and practices golf in the backyard, which is basically a four-hole par-3 course that Woods called “a short-game facility.” Or he heads over to the nearby Medalist Golf Club, playing with McNamara and sometimes rounding out the foursome with the likes of Dustin Johnson, Rickie Fowler and Rory McIlroy.

Or he goes to eat at his restaurant, The Woods Jupiter, billed as a “legendary sports bar experience.” (Woods Burger: Prime ground beef or bison with avocado, balsamic onions, lettuce, tomato on a brioche bun, with mozzarella or cheddar, $18.) Herman was hired in 2014 to design it and oversee its construction and operation. Now she lives with Woods, and the restaurant is a regular hangout, the site of company meetings and parties for Woods’s mother and his children.

Nothing about Woods’s life is entirely normal, but there are understated aspects that might surprise people. Maybe the best way to put it: His private jet is usually pretty empty.

He has no entourage, really. Woods has no swing coach. No mental coach. No driver. He travels with no masseuse or physical trainer, no personal assistant or gopher, no assortment of hangers-on that adorn those far less rich and famous. If he stays in a house rather than a hotel, he will bring his chef.

One who is always nearby as Woods practices is McNamara, a scratch golfer who has known Woods since both played youth golf in Southern California. McNamara is a sounding board, not a swing coach. He offers his assessment only if Woods asks.

“I know him, and I know what it looks like when it’s right, and I know what it looks like when it’s wrong,” McNamara said. “If I know what to look for, I can help.”

Woods split from his latest coach, Chris Como, in late 2017. His motto now is to swing away from pain. A coach’s tweaks could interfere with that. As long as his swing holds up, Woods plans to go it alone.

Lean and bald, McNamara sometimes gets confused for Joe LaCava, Woods’s caddy. LaCava spent 20 years with Fred Couples and joined Woods in 2011.

On one hand, his tight-knit company and his small traveling party — Herman, McNamara and LaCava, sometimes company spokesman Glenn Greenspan and occasionally Woods’s children — demonstrates what those close to him say about him: Woods is a low-maintenance superstar. On the other, perhaps it makes life easier to control.

If you were in northern New Jersey that week and saw a white BMW i5 with decals on the side that read “Official Vehicle The Northern Trust,” and did a double-take because the driver looked like Tiger Woods, it probably was.

He drives the courtesy car, always.

Then it is back into the bubble. When he went back to the house he rented for the tournament, what did he eat? How did he exercise? Did he watch TV, play video games or read? Skype his children? Make business decisions? Take Bugs, his Border collie, for a walk?

It is not for us to know. Privacy.

So you find the little things hiding in plain sight, like the tiger head cover on his driver with the threaded script. (His mother buys him a new head cover each year and sews “Love Mom” onto it in Thai.) Or the string around his left wrist. (It’s a Buddhist string bracelet, blessed by a monk.) Or the watch and red-and-white beaded bracelet he puts on soon after he finishes playing. (A Rolex and a bracelet made by his daughter that was red and black, but if you look closely almost all the black has chipped away to white.)

These are things he is willing to reveal, subtly or unintentionally, things that turn two dimensions slightly, so slightly, to three.

Tiger Woods is back, at 42, in 2018, far more than a memory, in good humor but keeping most of his thoughts to himself. He is a renewed but older man in a different age, forever recognizable from a distance.

Welcome back, Tiger, the people shout, waiting for a response.

John Branch is a sports reporter. He won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing for “Snow Fall,” a story about a deadly avalanche in Washington State, and was also a finalist for the prize in 2012. @JohnBranchNYT

- The Plot to Subvert an Election: Unraveling the Russia Story So Far

- Trump Says if Attack on Kavanaugh Accuser Was ‘as Bad as She Says,’ Charges Would Have Been Filed

- The Brothel Empire and the Ex-Detective, Always One Step Ahead of the Law

- Dianne Feinstein Rode One Court Fight to the Senate. Another Has Left Her Under Siege.

- China’s Sea Control Is a Done Deal, ‘Short of War With the U.S.’

- Sloan Kettering’s Cozy Deal With Start-Up Ignites a New Uproar

- Hard-Line Vietnamese President, Tran Dai Quang, Dies at 61

- Opinion: How Strong Does the Evidence Against Kavanaugh Need to Be?

- Opinion: Making Tariffs Corrupt Again

- Ice Surveys and Neckties at Dinner: Here’s Life at an Arctic Outpost

Advertisement

The article "Tiger in Twilight" was originally published on https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/07/sports/golf/tiger-woods.html?partner=rss&emc=rss