Rory McIlroy Is the Golfer Who Juggles. Or Is it Vice Versa?

At age 29, McIlroy is trying hard to make his life more than just an extension of the golf course. He seems to be succeeding.

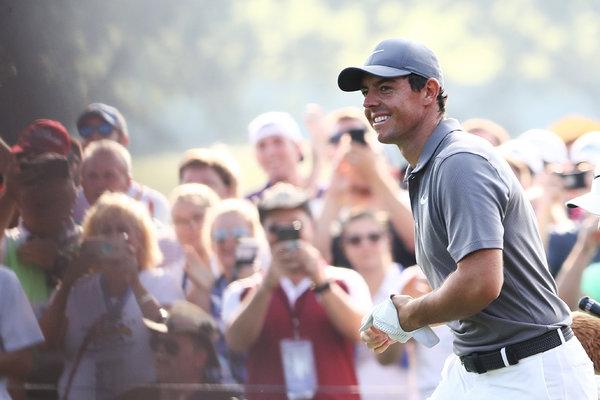

Rory McIlroy during the P.G.A. Championship in St. Louis last month. His last victory in a major event came in the same tournament, back in 2014.CreditCreditJamie Squire/Getty Images

Supported by

ST.-QUENTIN-EN-YVELINES, France — Rory McIlroy is straddling two continents, two tours and two colliding worlds — the celebrity and the secular. It is a lot to balance, and this year he has sometimes staggered under the weight of expectations, even taking up juggling at the advice of a doctor friend, who suggested it as a stress-relieving, focus-sharpening exercise.

After he pored over YouTube instructional videos, McIlroy took three balls and “literally spent all night juggling,” he said. By the next morning, he could complete 10 cycles without dropping a ball. If only life itself was that simple.

Still, McIlroy strides ahead, seeking to be both a performer on the world’s stage and a person fully engaged with the world. Instead of some monastic routine when he is competing — room-service chicken every night, egg whites each morning and nothing but golf in between — McIlroy tries to revel in what the rest of life offers. He plays soccer with friends — or he used to until he ruptured a ligament in his left ankle on the field — orders a glass of wine at dinner while trying trendy restaurants and generally seems more intent on building a life instead of just a legacy.

“I don’t want this to define who I am,” McIlroy said, referring to his golf career. “And some people have let that happen. I get it. If I am as good as I want to be, people will just see me as a golfer and that’s totally fine. But I guess I just never want to see myself as that.”

McIlroy won’t turn 30 until May, but he already has been through a closet full of identities: prodigy, political pawn, half of a power couple, United Kingdom golf royalty, and the one that never was a comfortable fit, the next Tiger Woods. McIlroy turned pro at 18, and by his 23rd birthday he had run away with a United States Open in Tiger-esque fashion and had collected six professional victories worldwide, including one major, two fewer than Woods at the same age.

He became the third player, after Jack Nicklaus and Woods, to win four men’s majors before his 26th birthday. Four years later, he has yet to capture a fifth major and to golf insiders, his game has become a teaser wrapped in a puzzle inside an enigma.

McIlroy comes into this weekend’s Ryder Cup as neither the highest-ranked player on the European team (Justin Rose is, at No. 2) nor the squad’s heartbeat (Sergio García); neither its reigning major champion (Francesco Molinari, British Open) nor its most outgoing 20-something (Jon Rahm). Instead, at the moment, McIlroy has a conspicuously low profile for someone playing in his fifth Ryder Cup, with five top-three finishes in 21 worldwide stroke-play starts this year.

And yet, at any moment, he can take over a tournament.

“When Rory plays his best, he’s the closest I’ve seen to the Tiger Woods I watched play for 10 years,” said the South African Trevor Immelman, who held off Woods to win the 2008 Masters. The difference, Immelman added, is that Woods maintained that level for a decade while McIlroy “plays that way three weeks every two years.”

The shadow cast by Woods has been particularly hard to shake for McIlroy, who rejects the long-running narrative that he set out as a boy to become Woods’s heir apparent.

“I grew up wanting to be a great golfer, to be as great as I could be,” he said.

But he maintains that he has never burned to succeed at the expense of everyone and everything in his life. “That’s not a great way to live,” McIlroy said. “You have to see the bigger picture.”

McIlroy’s level of stardom, though, typically requires a focus that narrows one’s vision until the only thing that can be seen is the next trophy, the next conquest, the next opportunity. Fame, fortune and power are the ultimate acquisitions, but they can form a Bermuda triangle of success, and by his mid-20s, McIlroy felt lost.

From there, came a personal transformation. It has led him to become a voracious reader and a practitioner of meditation and all of it can be traced to 2014, the year he abruptly ended his engagement to the tennis star Caroline Wozniacki after the wedding invitations had been mailed.

A year and a half later, he became engaged in Paris to Erica Stoll, who as a PGA of America employee had been instrumental in McIlroy’s making his tee time at the 2012 Ryder Cup outside Chicago after he got his time zones crossed.

McIlroy describes Stoll as a calming presence, a low-key booster of his career who is content to blend into the background. Among other things, Stoll takes advantage of their world travels to broaden his palate. The week of the BMW Championship, she reserved them a table at Philadelphia’s Spice Finch, run by Jennifer Carroll, who gained fame on the culinary show “Top Chef.”

The next day, out on the course, a fan shouted at McIlroy, asking him how he enjoyed his wine with dinner. “Jeez,” McIlroy said later, feigning indignation. “I only had one glass.”

Friends of McIlroy say he never has seemed more content. The four-time major winner Ernie Els, whose Jupiter, Fla., house McIlroy and his wife bought this year, often crosses paths with McIlroy when they are both in Florida. In an observation echoed by others, Els said, “Every time I see him he’s in a good place.”

But there are moments when the results-obsessed culture of professional sports leaves him out of sorts. Before last week’s Tour Championship he was asked by a reporter if he was upset about the way he had played in his previous start, the BMW Championship. McIlroy has fielded a version of that question ever since he fell short at the Masters this year and failed to become the sixth golfer — and the first since Woods in 2000 — to complete a career Grand Slam.

Irritation crept into his voice as he replied that he was happy with his progress on the course.

“It’s not all about results,” he said to the reporter. “That’s what you guys don’t understand. It’s about process. It’s about getting better. It’s about the bigger picture.

“I will play 500 tournaments in my career, so one golf tournament is not going to make or break it,” he added.

At the Masters, the BMW Championship and the Tour Championship, McIlroy played the final round in the last grouping. This season he has been in that position six times over all, and in each instance he has slid down the leader board rather than triumphed. On Sunday, of course, he got left behind by a rejuvenated Woods, who won for the first time in five years.

At his pre-Ryder Cup news conference on Wednesday, McIlroy was asked if he experienced “any element of intimidation” during Sunday’s final round, with Woods on the march. “That East Lake rough was really tough, yeah,” McIlroy said with a hollow laugh. Because he spent so much time hitting out of the trees, he added, “I couldn’t really see what was happening too much.”

The answer was vintage McIlroy: even when his pride is pierced, he is willing to poke at himself. It is why McIlroy is widely considered one of the best interviews in golf. That, and because he never settles for one-sentence answers when expansive paragraphs will do. He blends earnestness with impishness, the vulnerabilities in his comments sometimes belying the bravado of his bouncy walk.

On occasion his openness has gotten him in trouble. In 2012, McIlroy, who is from Northern Ireland, told The Daily Mail that even though he represented Ireland as a junior golfer, he was torn on whom — Britain or Ireland — to represent at the 2016 Olympics, when golf would be making its return. “I have always felt more of a connection with the U.K. than with Ireland,” he stated.

McIlroy’s comment drew sharp criticism in Ireland, and when it came time to settle on a country, his choice was to skip the Olympics altogether. In any case, the question over national loyalties has since given way to the Augusta National question. At the recent Dell Technologies Championship, the second FedEx Cup playoff event, McIlroy fielded an inquiry about his mental and physical preparation for the 2019 Masters, never mind that the first round was more than 200 days away.

Over those 200 days, McIlroy would no doubt like to dwell on other parts of his life, a sentiment familiar to Michael Phelps, a 28-time Olympic medalist who participated in a pre-Ryder Cup celebrity match and can appreciate the trickiness of trying to evolve as a person when the public just wants you to perform. “The biggest thing for me was finding that comfortability in my own skin,” Phelps said, “of actually looking in the mirror and liking who you see.”

He added: “The biggest thing I had to do to get to that point was figure out what could I remove from my life to make my life more simple.”

McIlroy said he found his own guide for pruning his life in the book, “Essentialism,” by Greg McKeown, with a subtitle that reeled McIlroy in: “The Disciplined Pursuit of Less.”

“It helped me learn to say, ‘No,’” McIlroy said.

McKeown said he understood what McIlroy meant. Both people and corporations, he contended in an interview, tend to start out with a clarity of purpose that fuels their success. But the realization of their ambitions can trigger an avalanche of opportunities and options that become obstacles in their path.

“What makes this so hard for a pro athlete like Rory or others is they have to start saying no to amazing opportunities that a year ago they almost certainly would have given their right arm for,” McKeown said. “When he says he has to learn to say ‘no,’ what he means is he has to say ‘no’ to better and better opportunities just to be able to stay sane and do his work.”

Or, as McIlroy said: “There’s a reason I try to keep my private life private.” He added: “I guess for me, my thing is: what is my goal in my career? My goal is to be a master of my craft.”

McIlroy is determined to own that goal, even if it means having to justify his journey to a public fixated only on where his golf game is right here, right now.

“I feel I’m having to defend myself all the time,” McIlroy said. “I don’t want to get my list of wins or achievements out and say, ‘Look, this is what I’ve done by 30,’ because that’s not who I am. But I’m like: ‘Guys, I’ve done pretty well so far. I know how to play this game.’ I’m finding it a little more difficult now than I have at other times. But I’ll get it back.”

- Collins and Manchin Will Vote for Kavanaugh, Ensuring His Confirmation

- The Nazi Downstairs: A Jewish Woman’s Tale of Hiding in Her Home

- Opinion: What It All Meant

- Opinion: The High Court Brought Low

- Susan Collins, Standing Alone, Makes Her Case for Kavanaugh

- Trump Engaged in Suspect Tax Schemes as He Reaped Riches From His Father

- Opinion: An Insidious and Contagious American Presidency

- F.B.I. Review of Kavanaugh Was Limited From the Start

- Melania Trump Raises Eyebrows in Africa With Another White Hat

- U.S. General Considered Nuclear Response in Vietnam War, Cables Show

Advertisement

The article "Rory McIlroy Is the Golfer Who Juggles. Or Is it Vice Versa?" was originally published on https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/28/sports/golf/golf-ryder-cup-mcilroy.html?partner=rss&emc=rss