Supported by

Playing Golf Alongside Tiger Woods Feels Different Now

By Karen Crouse

SAINT-QUENTIN-EN-YVELINES, France — Bryson DeChambeau began chirping in Tiger Woods’s ear as soon as they walked off the first tee box. It was the third round of the Dell Technologies Championship this month at the TPC Boston and the first time the two had been paired in a tournament. Woods, his stony mask in place, said nothing at first.

Players who competed against Woods in his prime, when he ruled the game of golf, would have recognized that look. They had learned to give him space. And if they hadn’t, Woods could count on his then-caddie-slash-bouncer, Steve Williams, to convey the message, however he saw fit, that Woods was not to be disturbed.

Brandt Snedeker, 37, who turned professional in 2004, said he couldn’t imagine an opponent like DeChambeau initiating small talk with Woods between shots 15 years ago. “I don’t think Stevie would have let that happen,” Snedeker said.

But DeChambeau, who was 3 years old when Woods won the first of his 80 PGA Tour titles, didn’t know any better. The dominant Woods was a cartoon superhero he watched on television. By the time DeChambeau played with him in Massachusetts, Woods had been rendered mortal by a battle with a damaged spine and DeChambeau, 25, saw him not as a living monument to tiptoe around but as a human search engine in which to plug questions.

So like a child walking home with a parent after the first day of school, DeChambeau blithely kept talking until Woods glanced back — and his mask slipped. He smiled and spoke. The two exchanged conversation throughout the round.

“It’s always fun picking his brain a little bit,” said DeChambeau, who has played several practice rounds with Woods during tournament weeks this year. “Every once in a while he tells me, ‘Dude, what are you doing?’ I’m just like, ‘I’m trying to get better, man.’ ”

Woods’s demeanor has changed in many ways during this comeback season. He has smiled in defeat, saying he was grateful just to be playing again after four back operations in three years. On Sunday at the Tour Championship, when he clinched his first title in five long years, Woods came close to tears and punctuated the day not with one of his aggressive right uppercut fist pumps, but with his arms raised in a victory V.

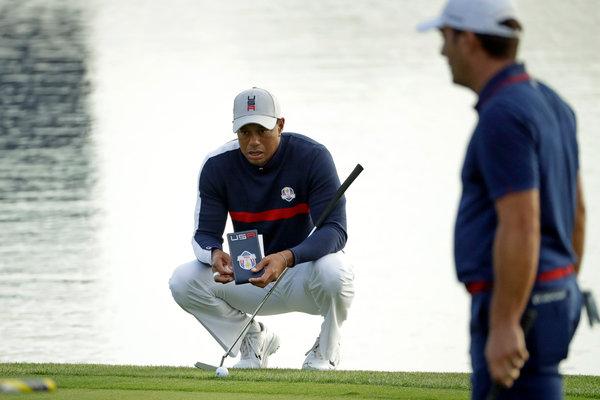

Among his peers, in particular, the self-contained Woods has become more of an arms-open-wide guy. That may benefit him at the Ryder Cup this weekend in France, where he will compete with the United States team for the eighth time overall and the first since 2012. It is the rare golf arena where Woods has blended into the scenery, perhaps because the Ryder Cup required collaboration with players he routinely bent to his will with a steely stare.

“He wasn’t the most friendly guy, but why should he be?” said Adam Scott, the Australian who took the No. 1 world ranking from Woods in 2014. “He created this thing around him where it was intimidating for everybody.”

Woods said he was always cordial between shots when he was competing alongside friends. One such player, Ernie Els, 48, said that was true but only to a point.

“If we were playing together the first and second rounds, we’d talk a lot,” said Els, a four-time major winner whom Woods sought advice from in 1996 before he decided to drop out of Stanford and turn professional. “But as the intensity of the event grew bigger, we’d talk less and less.”

Els was paired with Woods for the final 18 holes of the 2000 United States Open, which Woods won by 15 strokes. The two didn’t exchange a single word during the round.

That’s not unprecedented in professional golf, where decorum dictates that players in the zone, like pitchers throwing a no-hitter, be given their space. What made it unusual was that Woods practically lived in the zone.

“The killer Tiger,” as Snedeker described Woods at his peak, was great with other players in warm-ups before a round. “On the range, the putting green — totally fine,” Snedeker said. Then the round would begin, Snedeker added, “and he was going to get in his zone, and he wasn’t going to be outgoing and welcome you into his zone.”

Woods’s overall record in Ryder Cup play — 9-16-1 in foursomes and four-ball matches and 4-1-2 in singles — may reflect his lack of a dimmer switch for that intensity and his history as a man apart.

He and Phil Mickelson, 48, played together at the 2004 Ryder Cup, with disastrous results, losing their first two matches in an eventual rout by the European team.

Mickelson said recently that it was difficult to be paired with Woods in those days, because his game possessed no weak spots for a partner to shore up.

“You’d let him do all the work because he’s so good,” Mickelson said. “And you don’t get focused in on your own game.” Mickelson described the dynamic as “almost a diffusion of responsibility” that turned Woods’s partner, however subconsciously, into a spectator.

It was probably not easy for Woods, either, said Snedeker, who was a teammate of his on the 2012 Ryder Cup team: “I’m sure Tiger felt like he had to play better to help his teammate out.”

Woods didn’t even have to swing a club to help the United States team during part of last year’s Presidents Cup matches in New Jersey. In his role as an assistant captain, he stood off the green, in the peripheral vision of Si Woo Kim of South Korea, who missed a three-foot putt to extend a foursomes match. Kim said recently that he was “a little more nervous” because Woods was watching.

“He knows he affects the people that are around him when they are not used to playing with him,” said Jordan Spieth, a member of the U.S. Ryder Cup team, “and so he knows it’s an advantage having him around.”

As a player this week, Woods may still intimidate his opponents, but around his teammates he figures to be the same approachable leader he morphed into as an assistant captain at the event in 2016, when he shared his knowledge freely and encouraged the American players to tap into his experience. He has shown them a side that older players were treated to only in small glimpses, such as when Bubba Watson, now 39, played in a tournament in Japan years ago and bonded with Woods over video games.

But the week after the Ryder Cup, the calendar of the golf season turns over. Whenever Woods returns to competition — most likely not until the beginning of December at the event he hosts in the Bahamas — it will be interesting to see which Tiger the other players will face.

Will it be the collegial Woods who chatted with DeChambeau at TPC Boston and with Rory McIlroy on Sunday at the Tour Championship? Or the Woods who was walled off from the world and unnerved opponents just by showing up? Woods told a friend last year that he yearned for the younger players to feel the heat of playing the back nine of a tournament on Sunday with him holding the lead, a scenario that played out at the Tour Championship.

“A lot of these guys had not played against me yet,” Woods explained. “I think that when my game is there, I feel like I’ve always been a tough person to beat. They have jokingly been saying that, ‘We want to go against you.’ All right. Here you go.”

Playing with the lead Sunday, Woods took a conservative approach and let McIlroy and Justin Rose, his two closest rivals going into the final round, beat themselves, which they did, covering the final 18 in a combined seven over. It felt eerily like 2008 once more, when Woods’s opponents knew he was going to win and he knew that his opponents knew that he was going to win.

“It was a different vibe around Tiger at that point, and he used it to his advantage,” Scott said.

Billy Horschel ended up as Woods’s runner-up at the Tour Championship, finishing two strokes back after carding a closing score that was five better than Woods’s 71. As Horschel walked to the 17th tee at East Lake Golf Club, he crossed paths with Woods, who was striding the 14th fairway. Horschel thought about saying something to Woods, but then he saw his expression. Horschel stopped and let him pass, like a tennis player giving way to another on a changeover, and never uttered a word.

Why?

“Tiger looked like the old Tiger,” Horschel said.

An earlier version of this article inaccurately described the number of major tournaments won by Ernie Els. It is four, not five.

- Collins and Manchin Will Vote for Kavanaugh, Ensuring His Confirmation

- The Nazi Downstairs: A Jewish Woman’s Tale of Hiding in Her Home

- Opinion: The High Court Brought Low

- Opinion: What It All Meant

- Susan Collins, Standing Alone, Makes Her Case for Kavanaugh

- Trump Engaged in Suspect Tax Schemes as He Reaped Riches From His Father

- Opinion: An Insidious and Contagious American Presidency

- F.B.I. Review of Kavanaugh Was Limited From the Start

- Melania Trump Raises Eyebrows in Africa With Another White Hat

- U.S. General Considered Nuclear Response in Vietnam War, Cables Show

Advertisement

The article "Playing Golf Alongside Tiger Woods Feels Different Now" was originally published on https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/27/sports/golf/tiger-woods-ryder-cup.html?partner=rss&emc=rss