Editor’s note: In celebration of Golf Digest’s 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published. Catch up on earlier installments.

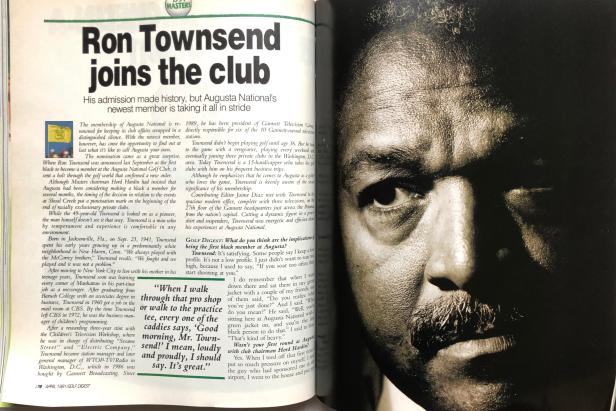

Ron Townsend was 49 years old when plucked from the executive ranks of Gannett as the solution to Augusta National’s membership problem in September 1990. The Shoal Creek controversy had shined a spotlight on racial discrimination at private clubs across the country, and golf boards scrambled to find black golfers to make members. As the most elite of all golf clubs, Augusta National could choose anyone, and its chairman, Hord Hardin, insisted that he’d been considering the move for several months. As the editors wrote at the time, “The timing of the decision in relation to the events at Shoal Creek put a punctuation mark on the beginning of the end of racially exclusionary private clubs.”

Born in Jacksonville, Townsend spent his early years growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood in New Haven, Conn. He moved to New York City to live with his mother in his teenage years, graduated from Baruch College with an associates degree in business, got a job in the mail room at CBS, rose to become the business manager of children’s programming at CBS and eventually the president of Gannett Television Group. He was an every-weekend golfer, belonging to three clubs in the Washington, D.C., area, and playing to a 15-handicap.

What’s most remarkable about Jaime Diaz’s interview with Townsend was that the club allowed it to happen at all. Members famously are not permitted to speak publicly about the club, as only the chairman “speaks for Augusta National,” but no doubt in this case Chairman Hardin saw the historical significance of Townsend’s membership for not only the club, but the game and posterity. Augusta National was slow to extinguish discrimination—it wasn’t until 1974 that the first black pro, Lee Elder, was invited to play in the Masters, and women did not become members until 2012—but on the issue of race, the club has since been admirably progressive compared to other elite clubs. As of this writing, there are at least seven black members, including former U.S. Secretary of State Condi Rice and former Pittsburgh Steeler Lynn Swann. (Rice also did an interview with Golf Digest when she became a member: https://www.golfdigest.com/story/condoleeza-rice-interview). Ron Townsend will be 78 when the Masters is played this year. This story first appeared in April 1991. —Jerry Tarde

***

Golf Digest: What do you think are the implications being the first black member at Augusta?

Ron Townsend: It’s satisfying. Some people say I keep a low profile. It’s not a low profile. I just didn’t want to soar too high, because I used to say, “If you soar too often, they start shooting at you.”

I do remember that when I went down there and sat there in my green jacket with a couple of my friends, one of them said, “Do you realize what you’ve just done?” And I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, you’re sitting here at Augusta National with a green jacket on, and you’re the first black person to do that.” I said to him, “That’s kind of heavy.”

Wasn’t your first round at Augusta with club chairman Hord Hardin?

Yes, When I teed off that first time, I put so much pressure on myself. I met the guy who had sponsored me at the airport, I went to the house and put my stuff up, changed, and went to the grill and met Hord right there. I sat down and had half a sandwich with him. And I was advised I was going to be playing with him. He was going to be driving the cart.

This was the opening day. I knew a couple of the people there, and I met folks. It was a little cloudy, so everyone said, “Let’s play as soon as we can so we can get the 18 in before it rains.”

So I come out of the grill, and I see one caddie, three caddies, five caddies, seven caddies, all black—it was as though they were saying, Here he is. So I went over and I shook each of their hands and said, “I’m Ron Townsend.”

There are about 40 members there, and, obviously, playing with the chairman, you tee off first. So Hord hits it, boom, down the middle. He can’t see that far, so he’s saying, “Where’d it go? Where’d it go?” It’s about 190 yards down by the trap to the right. Obviously I’m hitting next and took a fairly fluid practice swing, recognizing exactly what was happening at that very moment. The first time I played it there was no lunch ball, no mulligan—you hit the first ball, and that’s it. So, you know, you envision missing the ball or hitting it 30 yards down there.

I got over the ball and shifted my weight a little bit and hit a career tee shot. I picked up the tee, moved aside and waited for the next batter. It was a fantastic feeling. I’ve played that hole 15 times, and I’ve never hit it better. I hit it up the left side, rolled up the top of the hill, and I’m so pumped now I asked the caddie, “How far is that trap there?” He said, “You can’t get there.” I knocked the ball into the trap. It took me two to get out. I double-bogeyed No. 1.

On the second hole, now I’m really pumped because I’ve got the first hole under my belt. I hit a career shot down the bottom of the hill. I parred the second hole. The caddie walks up to me and said, “Mr. Townsend, welcome to Augusta.” At this point I’m saying, “Bring ’em on.”

Did you feel under scrutiny that first day?

No. No. You know what, it was just the opposite. Most of the guys are over 50, and as a matter of fact, being 49, I was called a youngster. They were there to play golf. They were all very cordial, and all came over and introduced themselves slowly because they recognized that I had to look at them a while to remember names. And I’ve been back, and I see a lot of them and wave. Frankly, I would have been very uncomfortable if they’d been patronizing, because that’s not my style. Again, these are successful businesspeople who have been around and been in many situations. As far as they’re concerned, I’m just another businessman.

I don’t know what role the members played in my membership because the course is really run by one person—it used to be Cliff Roberts, and now its Hord. My sense is that there wasn’t a vote. I don’t know; I’ve never asked. I just know I was offered to become the 300th member.

What has been your impression of Hord Hardin?

You know what? He sounds and looks like a crusty old man, but Hord is a mellow, mellow man. I’ve had dinner with him, and he’s a very gracious person, very open, not threatening. He’s just a nice, nice man. The first impression of him when you read about him in the paper or you see him on the Masters telecast—he’s nothing like it.

Did you have any second thoughts? Or did you feel comfortable right away about joining?

Well, I‘ve been there six times now, and each time I go there I feel better about it. I feel better about the play, the comfort level. Each time I go there with a guest, I’ve made a friend for life, because it’s such a great experience. Playing golf at the golf course, having dinner there, playing the Par-3 Course, the large course. The last time we there, about three weeks ago, it was a Saturday, about 55 degrees, and we were the only foursome on the course. And one of my guests looked at me and said, “Can you believe this?”

I was on my way to New Orleans, so we stopped by and spent the weekend there. One of the guys I played with is a business associate in New York who’s overweight like the rest of us, probably 30 or 40 pounds overweight, so I asked him, ”Do you want a cart?” He said, “A cart at Augusta National? I’m going to walk, and you’re going to walk.” And we walked 36 holes. He’s like a 22-handicap.

What has been the reaction of your friends?

Awe—just at the conditions of the course, the quality of the staff. But, you know, two or three of my buddies know they would never get there without me, so they owe me! But frankly, if they were ever to give me anything, I’d just like more strokes.

There has been some speculation that because nearly the whole staff is black, a black member or guest would feel uncomfortable.

That’s a possibility. But you know what? The way they treat their staff, that’s important, too. They treat them with respect. I mean, some of them call the staff Mister. And it’s the South, so let’s face that fact. Also, a lot of these people, like the wine steward, are proud. I was proud to see this black wine steward who would take you down to the wine cellar and tell you anything about the vintage. Or Ellis Dent, Jim Dent’s uncle, who is the maître d’ there.

These are very proud people and there’s no “Yah-sir” going on there. But it just so happens that they are all black. And frankly, I enjoy Southern cooking, and thank God for that.

Did you get a sense from caddies of what your membership means?

Well, when the caddies came out, I shook their hands, and you could sense the pride there. Again, not all have been out with me, but you sense something. One caddie told me that he’d caddied for Lee Elder, and the reference was that, “You’re not the first black I’ve caddied for, but you are the second.” Yet it was said in a very positive way. When I walk through that pro shop or walk to the practice tee, every one of the caddies says, “Good morning, Mr. Townsend!” I mean, loudly and proudly, I should say. It’s great.

How does the atmosphere compare with other clubs—is it loose or formal?

Loose. The average bet is not a lot of money. The no-tipping policy is made very clear. It’s very clean. I like to smoke a cigar, particularly when I play golf, and I always take the wrapper and put it in my pocket. At some courses you might take the cigar and throw it over in the bushes, but I’ve never done that at Augusta. The caddies carry around the dirt [to fill in divot holes], and I put it in that.

What was the process of your becoming a member at Augusta? How did it start, and when did you first know you were being considered?

I first knew when the chairman, CEO and president of our company called me and indicated that there were two gentlemen who wanted to come in and talk to us about Augusta National. My comment was something like, “What for?” It was the furthest thing from my mind.

You’d never considered being a member there?

No. I thought about Augusta National. I used to say that I’d like to go to St. Andrews, and it’s still something I want to do. During the years I was at CBS, I never expressed interest in going to the Masters. It wasn’t something I wanted. I’ve watched it as I’ve watched other tournaments, recognizing the history and all. But it was only after I started reading a couple of books I got that I really began to realize what that place meant and what it was to golf.

Anyway, these two gentlemen came in, and we had a nice, cordial lunch upstairs in the dining room that lasted for about two hours.

It wasn’t supposed to be an interview. They didn’t fire questions at me. They’d already, obviously, checked out some things and had already called the chairman of our company. When they left, I had an indication that they were interested in me, and I made it quite clear to them that I was interested, and about a week or so later, I got a letter.

So you were happy to be considered for membership?

Oh, yeah. I never hesitated. When I was asked if I would consider, I said, “Absolutely.” I mean, I didn’t pause. I wondered later, Should I have done that? But it was like proposing to your wife and saying, “Will you marry me?” and she says yes right away instead of pausing. It was an easy decision.

As a new member, have you had to take an oath of secrecy?

No. Apparently many people don’t know things because I’ve been asked by several folks. I felt that you’re not going to find out from me. I’d just rather leave it that way.

No one has come to me and said, “I understand that it costs a million dollars to join Augusta National.” The fact that many people don’t know must mean that [the actual cost] is not common knowledge, and I’m certainly not going to be the one to share it.

So there’s no debriefing or anything like that?

No. There are no meetings, no committees, which is the way the members want it. The guest policy is three at one time, and you cannot overlap guests. Those are not big things.

When did you begin playing golf?

I started playing golf late in life. My wife, who’s always a few steps ahead of me, bought me a set of golf clubs in 1975, and they sat in the garage for two years. One day we were going to go up to Wintergreen in Virginia with some friends of ours, and they said, “Bring your golf clubs.” We went up to this very plush resort and played Devil’s Knob, a challenging, mountainous golf course. I took some lessons and went out, and after about the third hole I said, “My God, where have I been?!” I was obsessed with the game the first time I played it. I’ve always said to folks, “If you play golf one day and you don’t come away saying, ‘God, I want to do it continuously,’ then it’s not for you.” Because it grabbed me just like that.

Just a moment. You took lessons and played the same day?

Yes, I took lessons that morning for an hour and then played that day. The guys were saying, “You don’t have to hit it out of the sand trap.” But I was so persistent. I must have shot like 200 the first time out. But I finished the 18 holes and lost a lot of balls. But they had advised me to buy a bunch of X’d-out balls.

That was my first outing of golf, and I came back here and joined the Washingtonian Golf Club, which had two of the most beautiful golf courses. They’re torn down now for development. Every Saturday and Sunday, rain or shine, I played golf those first three or four years. I mean, one day I played and it was 40 degrees. The lake was frozen over.

You obviously love the game.

Yeah. One of the greatest times I had was in 1982, when we went to London and played a semiprivate course that someone got me on. I met three guys at the course. We played six or seven holes, and it started to rain and thunder. They had wooden shacks out in the middle, and we sat there for two hours waiting for the rain to stop. Everybody’s telling war stories and golf stories and fish stories, and at one point it dawned on me that I’d just met these guys an hour ago and you’d have thought we’d known each other forever. I think that’s one of the beauties of the game. One of the things you can say about Augusta is, when you’re into that gate you’re all equal, no question.

When you were a New York City kid, what did you think of golf from afar?

I’d never realized the sport was also a way to meet interesting people. People talk about deals and business being done on the golf course, but I rarely do it. Like, you don’t sit down at a table and start negotiating. I’ve heard people say, “I was playing golf with so and so the other day … ” So there is a social connection, and there may be some social rewards, but I don’t think you can identify them. I think it just kind of happens, through osmosis.

Lots of people that I’ve spent four hours on a golf course with, I probably would never have spent 15 minutes with. In that respect, there are relationships formed and networks established. Because somebody will always remember that 20-foot putt you sank, or that chip-in, or that you won three bucks from them—which is the craziest thing about golf.

As a black man starting to play golf, what was your attitude about the racial baggage that comes with the game?

Well, I played in this area, Washington, D.C., at the Washingtonian Golf Club and Indian Spring, and I can say that on any given day at Washingtonian, if there are 150 golfers there, 50 of them are black. So my sense was that there were a lot of blacks playing golf at a lot of courses throughout this country.

Carl Rowan, a good friend, talks about the days in the late ’60s when he and a couple of his buddies were the first to play at Indian Spring. Rowan and some folks actually integrated Indian Spring Country Club. That’s 20 years ago. And as I started to travel to places on the West Coast and in the Southwest, I didn’t see as many blacks playing. But I had the opportunity to go to the best golf courses in the country because I was on business.

Have you felt discrimination in golf?

I’ve gotten peculiar looks from the caddies—black caddies. It’s been like, What are you doing here? But, no, I haven’t felt discriminated against in golf. I’ll tell you, it was exactly the opposite at Augusta with the guys. I mean, I felt good, and I know they felt good. You can sense that; you can feel it. I think it’s been a very great experience on both sides, and, I think, relief on their side.

I got a letter from two black student golfers in New York, Jamaica High School, who said they were so glad to know that now they can play golf anyplace they want to. Obviously that’s not the case. Hopefully, 10 years from now that will be the case—unless people have decided we’re going to leave it the way it is, and if you don’t like it, then screw you.

I always felt that if I was told I couldn’t go someplace, then I wanted to go. I object to being told I can’t do something, especially if it’s only because I’m short, fat, tall, skinny, the wrong color or the wrong religion. And I probably will only do it for one time. I just don’t think that there should be anything in this country, or this world for that matter, that if we can afford it we should not have the opportunity to participate in.

How much discrimination have you felt in your life?

Oh, my kids ask me that, too. I remember being infuriated as a boy in Jacksonville when I’d ride on a crowded bus with my grandmother, who worked all day as a domestic, and maybe some young white kids would get on, and she would immediately jump up to give them her seat. I’ve had several situations where the cab driver didn’t stop. I’ve been in the wrong restaurants at the wrong time. But in most of those situations, I’ve always been with someone else, and I’ve never been asked to leave those places. But you know when you’re not welcome someplace. I can’t remember the last time it happened, but it’s every now and then. I say to myself, I wonder if he knows who I am.

You really get defensive about the darned thing. Because of the circles I travel in, it kind of transcends race. I mean, racism is alive, I’m not naïve enough to say that it isn’t. But I hope it’s not well. But it is alive.

Should CEOs or very high-ranking executives be held accountable or held open to charges of hypocrisy, for example, if they practice equal opportunity employment in the workplace and yet belong to clubs that are exclusionary?

Well, I think a lot of companies have a policy that they won’t fund memberships to those kinds of clubs. I’m one who thinks that there are certain things you can legislate and certain things you cannot. And I’m not certain that I want anyone to tell me that I couldn’t do something that I really wanted to do. I think enlightened managers and enlightened CEOs would not put themselves in that position. In most of these situations, the company and the stockholders are funding the membership fees. I think you’re going to find fewer companies making dollars available for memberships in those kinds of clubs, primarily because of the sensitivities. But if some CEO decided that he or she wanted to go and spend his or her own money and be a member at so-and-so, I’m not sure whether that’s wrong. But I think that it’s the minority of people in those positions, and it’s shrinking.

I can remember a guy in Atlanta, Fred Ellarbee, who was a lawyer who worked for us. This is back in the early to mid-’70s. He used to belong to a city club in Atlanta. We’d go out and have dinner, and I’d say, “Fred, I want to go to your club.”

And he said, “Ron, I like you very much, I like your company and your business, but I ain’t no pioneer.”

And Fred was a friend, a good friend, and he would take me to the best restaurants in Atlanta, but never to a place where he was a member where they didn’t allow blacks.

But I never felt for one moment anything ill about Fred. My sense was, that’s the way he grew up in the South. One thing I appreciated was that he hired black attorneys and made one of them a partner, and that was a bread-and-butter issue.

I’ve been to Fred’s house; I’ve had dinner with him and his wife. Fred’s very gracious, and I spent the night there one night because I had too much to drink. But the fact that I couldn’t go to his club—it didn’t matter.

The symbolism of integrated clubs is important. We’re talking about the leaders in society to a large extent, and if their clubs are omitting a certain segment of society, doesn’t that reflect on the way society is run?

Yeah, I mean, it’s like the way a company runs. You want it to mirror society, mirror the community you are in. I agree with that, sure. No question about it. I suspect what’s happened is like everything else with our generation. In the next 10 to 15 years, a lot of those folks won’t be around. I think their sons and daughters, the ones who are coming up, are a lot more likely … whether it’s the Vietnam War or whatever, there are just certain experiences there that folks have that their parents didn’t have. I think we’re gonna have to keep pushing. I don’t believe it’s just gonna happen just because it’s the right thing to do. But I suspect there’s less ignorance now.

We’ll take Mr. Hardin at his word that he was looking for a black member prior to Shoal Creek—would you prefer that you had just been quietly chosen as that member without any fanfare?

Well, I am a member of a couple of clubs here in the Washington area, not sporting clubs but private clubs, and they have minority members. It was pretty exclusive, and I had to go through the process with my wife and had to meet everyone. It’s fine, and we take friends there. It would have been just as well if Augusta did it the same way. I was just saying, let’s focus on how my getting into Augusta is bringing other people in. Hopefully that’s happening. But yes, I could have been happier just getting in quietly, enjoying the course. But I’ve had a lot of fun with it, too. I have folks talk to me that I’d always chatted with, but they’re my best friends now. My line to everybody when they say, “When are we going to Augusta?” is, “You’re on the list. Don’t worry, you’re on the list.”

Do you think that your stature in your industry will improve through your membership at Augusta?

I’m fairly visible now, but things can only get better. I certainly will meet people. I had an opportunity to spend some time with [former Secretary of Defense] Melvin Laird when we went down with him on an airplane and played 18 holes with him. We had dinner with him and talked about the military buildup. It’s nice for me to be able to tell my colleagues something like, “Well, Melvin Laird said … ” Not name-dropping, but having someone with authority share an opinion.

How many times a year do you think you’re going to play or try to play Augusta?

Well, I don’t want to play it too many times and have it printed, because I already get comments from the vice-chairman, “Townsend, have you moved down there?!” There are four or five parties per year for members only, and I would like to make three of those. I’ve been down on the company plane with business associates, and one of the beauties of it is that it’s an hour and 25 minutes from here. You go down, play 36 holes, have dinner and get up the next morning and play 18 on the small course. You’re back, and it’s like a two-day turnaround. Those could be weekend trips, too, that don’t necessarily have to take you out of the office. I’d like to do it as many times as I can. I love the golf course and I love the place.

Do you think you would feel comfortable nominating another black for membership at Augusta?

I don’t know how to answer that. I read someplace that they’re looking at another black member for Augusta. Frankly, I hope they are. I haven’t had those discussions because it wasn’t appropriate—it certainly wasn’t the time for it. But I don’t want to be the only black member at Augusta or the only minority member. I would hope there will be many more black and minority members at Augusta, and I would hope that others would want that. I would say that if it looked like they aren’t ready for that to happen I would have no problem with it, but I would hope that others would want that. We’ll see.

The article "Augusta National's first black member - Golf World - GolfDigest.com" was originally published on https://www.golfdigest.com/story/augusta-national-s-first-black-member